Corporate Charters as Contracts in Dartmouth College

Marshall's Constitutional Innovation

In the August 25, 2025 edition, The Chancery Daily again takes up the novel dynamics introduced into Delaware corporate law by the conceptualization of corporate charters and bylaws as contracts between parties. This was a topic TCD had previously addressed on July 30, 2025.

On that earlier occasion, TCD took issue with the idea that corporate charters are contracts. This is an interesting issue with many important implications, so it’s a topic we’ll likely get several posts out of. Let’s start at the beginning, however,

As TCD notes:

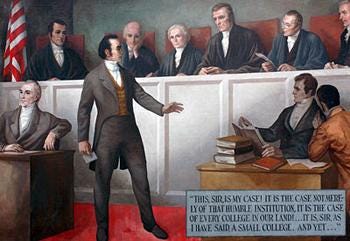

As to the conceptualization of corporate charters as contracts, it is true that Trustees of Dartmouth College v. William H. Woodward, No. 44, opinion (U.S. Feb. 2, 1819), ruled that a charter was a contract (i.e., between the King of England and the College's trustees). Importantly, as a consequence of the charter's status as a contract, the Court found that the State of New Hampshire could not alter the charter without the consent of the corporation.

… while one might accurately cite Dartmouth College as stating that the charter of a corporation is a contract, it should be observed that -- under conventional understandings of the Common Law of Contract (i.e., the law of consensual party agreement) -- "Contract" (with a Capital "C") isn't a label that one applies to deem something that is not a Contract to have the legal attributes of a Contract. The legal attributes of a Capital "C" Contract are conferred to an agreement formed by parties that satisfies certain requirements (e.g., capacity, meeting of the minds, exchange of consideration, assent of persons to be bound, etc.). If a corporate charter was adopted by parties who lacked capacity or without any meeting of the minds, or otherwise failed to comply with requirements for the formation of a Capital "C" Contract, there seems little justification for treating it as a Contract memorializing legal obligations between parties simply because it was styled as a "charter."

TCD cannot claim to have plumbed the factual depths of the (by some counts) 200-page Dartmouth College Opinion, but one surmises that a charter between the King of England and the College's trustees (in 1769) likely represented a bargain entered between the parties to be bound and probably satisfied the other standard requirements of contract formation.

TCD raises an important question about Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward (1819): namely, that while Marshall famously declared a corporate charter to be a “contract,” this label ought not, under traditional common law doctrine, to bestow upon a charter the full legal attributes of a Contract (with a capital “C”). In TCD’s view, unless a charter satisfies the requirements of common law contract formation—capacity, mutual assent, consideration, and so on—then styling it a “contract” is a doctrinal stretch, perhaps even a category error.

This is a serious point, and one that is worth addressing, because it touches on a deeper tension in Dartmouth College between doctrinal contract theory and constitutional functionalism.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Bainbridge on Corporations to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.